Lecture 4: Inferential Statistics: Causation or Correlation?

Introduction

Introduction

In lecture number three, we review the use of descriptive statistics to answer questions such as: “What is the current state of affairs?”; “How often, how many, when?” An also I introduce the us of the correlation coefficient to assess “what is the association between two variables?” However, in many cases, to show that two variables have an association sometime is not enough. Associations only measure how the set of variables change toguether, but, they do not say anything regarding the direction or magnitude of the relationship. To say something about the direction, means to discover if one varibles is the cause or determinant of another. Here, there is a clear order in the relationship between two varibles, for instance, \(X \rightarrow Y\), represents that \(X\) is the cause or determinant of \(Y\). The magnitude of the relationship refers the measurement of the effect of \(X\) on \(Y\), for instance, if \(X\) changes by one unit how much does \(Y\) would vary?

The distiction between a correlation and a causal relationship between two variables is not only important but necesarry in many applications. Imagine for intance the development of a vaccine or an important policy prescription. Obviosly, the research that backs-up these developments will impact the life of many people. Therefore, we would like to make a precise inference to be able to claim with robustness the magnitude and the direction that exist between variables. An asociation between two variables is not strong enough to draw conclusions about the population of our interest. In many cases we would like to move then from showing a correlation between variables to find which variable is the cause or determinant of the other. This kind of research is the central quest of econometrics and Data Science and has a special place in empirical economics.

Causality and Correlation

As it turns out, the kind of relationship between two variables is no so clear. As Data Scientist, we should proceed with scientific skepticism when we analyze the relationship between two variables. When we measure a correlation between two variables, we are merely assessing the association between two variables, but that is not the same as causation. To help you draw a line between an association, correlation and a causal relationship between two variables, I elaborate on some properties that causal relationships must have:

A Causal Mechanism

The development of Machine Learning and Big Data are pushing the boundaries between data-driven and theory-driven research (Maass, Parsons, Et Al., 2018). Indeed, there is nowadays a real debate on the power of Data Science to replace the scientific method:

Very large databases are a major opportunity for science and data analytics is a remarkable new field of investigation in computer science. The effectiveness of these tools is used to support a “philosophy” against the scientific method as developed throughout history. According to this view, computer-discovered correlations should replace understanding and guide prediction and action. Consequently, there will be no need to give scientific meaning to phenomena, by proposing, say, causal relations, since regularities in very large databases are enough: “with enough data, the numbers speak for themselves”. The “end of science” is proclaimed… Claude & Longo, 2017.

However, in Economics, we are skeptical about weather data driven methods can really be a substitute for theory driven research. With the advent of Information Communication Systems (ICT) and now Big data, are generating large volumes of information. The availability of all sorts of data, also pose a challenge of identifying meaningful relationships between variables. The issue is that more often than before, we can find out by chance pairs of variables that seem to be related, but in fact they are completely disconnected from each other. In Economics, there is long persistent concern about this kind of problem called spurious relationship between variables. In Layman’s terms, a spurious relationship occurs when a set of variables seem to have a relationship, however, they are in fact completely unrelated.

So then, what is the solution to avoid the trap of the spurious relationship between two variables? The answer is a well-defined and coherent theoretical framework. In fact, the main stream of methodology in economics, has always been about finding methods to prove economic theory and not the other way around. Although, that trend is changing, and some Data Scientist would argue that research is becoming more data driven, the fact is that in economics there is no substitute for a well-defined and coherent theory. The seminal work of Blaug (1992), takes a closer look at the developments of methodology in economics and argues that:

Methodology is study of the relationship between theoretical concepts and warranted conclusions about the real world; in particular, methodology is that branch of economics where we examine the ways in which economists justify their theories and the reasons they offer for preferring one theory over another.

An Exogenous Model

To argue that two or more variables hold a causal relationship, we must ensure that our models are exogenous. What does that mean? Well, to say that \(X \rightarrow Y\), requires that we control in the estimation all other factors that affect \(Z \rightarrow Y\) our dependent variable. If our theory suggest that \(X\) causes \(Y\), we must ensure that our estimation isolates well the causal mechanism. In other words, we must account jointly with \(X\) all the other \(Z\) determinants of \(Y\). If we fail to include all the variables that are systematically affecting \(Y\), we fall in the omitted variable bias (OVB) trap. OVB is common, because if there are variables that remain confounded or unobservable (\(Z\)), make it hard to distinguish if \(X\) determines \(Y\), or perhaps is \(Z\)? A graphical approach to understand OVB treats to a causal estimation is represented in the following diagram. Here we can see that our variable of interest \(X\) is indeed causing \(Y\), however, there is another variable (in the yellow region), \(Z\) that is jointly affecting \(Y\). Failing then to control for \(Z\) induces a discrepancy between the population parameter(s) and our estimate(s) called bias.

Unbiased model: $$Y=\beta_1 X+ \beta_2 Z+\epsilon$$

The classic example is the estimation of years of education (\(X\)) on income (\(Y\)). The problem is that we can measure really well the years of education, but other determinants like ability, motivation and number of hours of study are very hard to measure. Even if we have psychometric measurements of IQ, these metrics are only proxies of the latent ability at the individual level. A proxy means that is just an approximation of the real variable that remains or confounded or unobserved. The book of Stock and Watson, (2019), offers another example from the study of school grades (\(Y\)) and the student-teacher ratio. The intuition of the study is that if the student-teacher ratio is high, then the grades are low. The causal mechanism is that explains this negative relation is the lack of capacity of teachers to properly tutor many students. However, the estimation, suffers from OBV, because it does not account for the percentage of English learners in some schools. This is a problem because migrant children might require additional tutoring, given that they do not master the language. Another potential source of OVB is the lack of control of the time of the test. As it turns out, the time of the test can impact the scores, because in early morning and later in the evening the alertness may reduce.

A special type of OVB is called self-selection. Self-selection appears in an estimation when there are inherent characteristics of the unit of observation that affect the outcome variable (\(Y\)) but remain confounded or latent. This perhaps sounds quite abstract, so let’s give some examples to clarify the concept. Imagine that you are interested in estimating the effect of education quality (\(Y\)) on the career success (\(Y\)), measured in monthly income. So you run a model and control for the different schools; among the sample you have graduates from Oxford, Harvard, Stanford and so on. Then in your estimation, it appears that indeed the higher the rank of the university (for the World University Ranking) the higher the measured salary of the graduates \(Y\). But wait, aren’t more able students also more likely to enroll themselves into highly ranked universities? Indeed, variables such as ability and motivation are very difficult to observe, and hence it is hard to determine if schooling from highly ranked universities causes latter career success. Although the association between university prestige and career success intuitively makes sense, most of the time we are only able to describe a simple correlation between the variables (Gonzalez-Sauri and Rossello 2022).. Another example, from studies of science and technology, is whether research collaboration causes higher research productivity? Similarly to the previous example, intuitively, we may expect that increments in the collaboration render beneficial exchanges between researchers that increase the overall productivity of authors. Similar to the previous example, intuitively, makes sense collaboration brings gains of human capital, division of labor and pooling of resources. However, we disregard, that these positive externalities from collaboration depend on the individual self-selection into networks or teams (Ductor 2015). The self-selection takes place because researchers do not connect or make partnerships with everybody randomly. But most of the time, a researcher’s own preferences in terms of discipline, research interest and other individual characteristics such as their personality are the reason behind the membership into different networks. Thus, it is hard to tell weather is collaboration the determinant of productivity or is it some other individual characteristics that help some researchers to be part of prolific networks.

A second source of endogeneity (opposite of exogeneity) is called reverse-causality. Reverse causality is a real problem in many datasets because there is some feedback mechanism \(Y \rightarrow X\) in which the dependent variable also affects the explanatory variable. A classic example in economics of this issue is presents in the functions of supply and demand. The issue is that \(S=P\) supply varies depending on the selling price, but simultaneously, the price is also changing according to the demand \(D=P\). This is an issue of feedback, in which the dependent variable (supply-demand), affects the explanatory variable (price) under equilibrium. This system of equations has a problem of reverse causality that is not so straightforward to solve. In graphical form, the problem or reverse causality is represented in the following way:

Unbiased model: $$S=\beta_1 P +\epsilon$$ $$D=\beta_2 P +\epsilon$$

A similar problem that poses a thread to exogeneity, is called circularity, and it happens when past realizations of a dependent variable have an impact on contemporaneous values. There are many examples of this problem in finance and time series econometrics. For instance, in macroeconomic estimations of the \(GDP_{t}\) it is crucial to include the previous state of affairs \(GDP_{t-y}\). Where \(t>y\) stands for a previous period, such that the current or contemporaneous \(GDP\) depends on the state of affairs of the last year. The problem of circularity in graphical form is described as follows:

Unbiased model: $$GDP_{t+1}=\beta_1 X + \beta_2 GDP_{t+1} +\epsilon$$

Nature of the data: Observational vs Experimental

If we think deeply about the exogeneity threads discussed in the last section (OVB, self-selection, reverse causality and circularity) we may see a common problem. Yes indeed, at the heart of the issue of endogeneity (opposite of exogeneity) there is a common problem of confounding factors. A confounding factor, in Layman’s terms, is simply a variable that we can’t get our hands on. Either because we do not have the data, we can’t measure it (OVB), due to a problem of self-selection or because our dependent variable has a form of feedback (reverse causality or circularity). All the listed problems, induce bias and yield an unreliable inference because at the backbone of the estimation there is a problem of confounding variables. Having confounding factors in an estimation is like cooking with an incomplete recipe, or analogous to having a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces.

This general issue of confounding variables is not easy to solve with the vast majority of the data sets that we can get our hands on. Indeed, the aforementioned threads to exogeneity may persist even in the most tidy and organize data from relational datasets (SQL for instance), surveys or administrative records. And unfortunately, the issue of confounding factors is not solved by increasing the magnitude and quantity of the data at our disposal. Even if we could collect Big Data that has millions of records using Web Scrapping algorithms, a large company or government agency, the problems may persist.

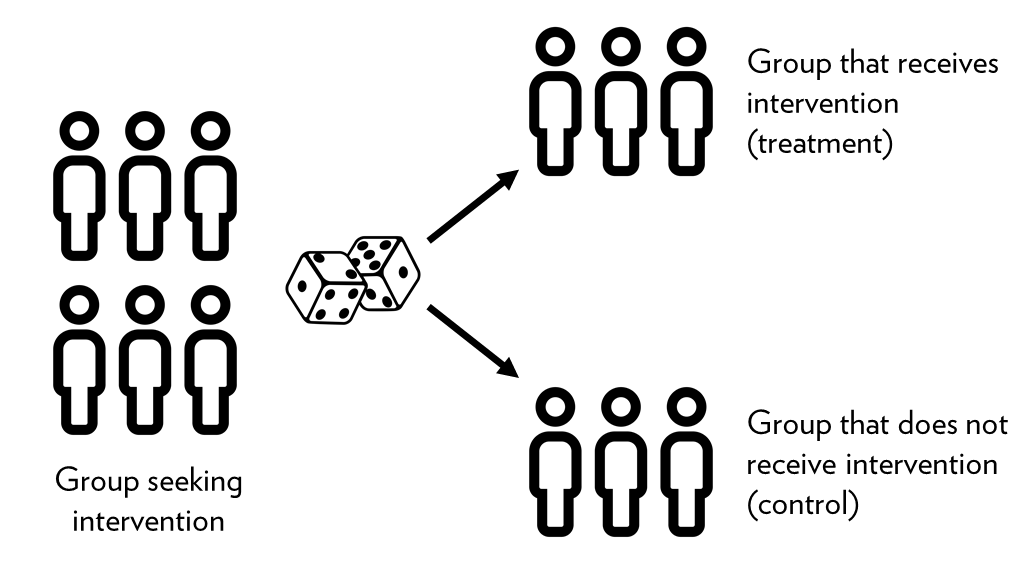

One way to solve the problem of confounding factors is to employ what has become the golden standard in Economics and Social Sciences is called Randomized Control Trials (RCTs). Data that comes from RCTs is called experimental data and is different from all data we can collect from other sources, generally called observational data. An RCT typically has a well-defined causal mechanism that directs the process of data collection to eradicate by design the problems of confounding variable. Indeed, the power of the RCTs derive from their power to isolate well the causal mechanism by virtue of a random assignment. In simple terms, the ideal RCT design starts by selecting at least two groups of similar units (individuals, firms, regions). These two groups must be similar in all characteristics such that any difference between them becomes insignificant on the averages. The comparison is then an “apples to apples” and not “apples to oranges”.

Source:Initiating an Experiment, Ch.4

Source:Initiating an Experiment, Ch.4

The heart of the RCT is changing randomly the circumstances that surround the causal-mechanism in one of the two groups, namely, the treatment-group. The randomized assignment has two main virtues, firstly, we eradicate the problem of self-selection by controlling which of the two identical groups receives the treatment. Keep in mind that the treatment embodies the causal-mechanism that we are aiming to showcase \(X \rightarrow Y\). The second benefit is that by changing the circumstances randomly, the variable of interest is most likely disconnected or unrelated to any other \(Z\) factor affecting the outcome variable \(Y\) of our research.

Examples

Chocolate consumption and Noble laureates

The study of Aloys LeoPrinz, (2020), studies the well known association between Nobel laureates and chocolate consumption. At first glimpse, when we look at the consumption of coffee and chocolate with the number of Nobel laureates winner, we can tell that there is a positive relationship. Using descriptive statistics, we can assess this easily with a scatter plot or correlation table.

library(ggplot2)

library(gridExtra)

library(dplyr)

choc_lauretes <- readRDS("choc_lauretes.rds")

grid.arrange(

choc_lauretes %>%

ggplot(aes(cholate_per_cap, no_nobel_lau)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = T),

choc_lauretes %>%

ggplot(aes(coffee_per_cap, no_nobel_lau)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = T),

nrow = 1

)

cor(choc_lauretes[, c(2L:4L)], use="complete.obs")

| cholate_per_cap | coffee_per_cap | no_nobel_lau | |

|---|---|---|---|

| cholate_per_cap | 1.00 | ||

| coffee_per_cap | 0.45 | 1.00 | |

| no_nobel_lau | 0.17 | -0.12 | 1.00 |

The correlation matrix shows that both chocolate and coffee have a positive association to the number of Laureates winners. The correlation of chocolate is to the Nobel winners is stronger than of the coffee. While looking at the scatter plot, we see that the trend indicates almost no relation between the coffee consumption and Nobel winners, however, we can observe a clear positive trend between chocolate consumption and Nobel Prize winners. Does chocolate consumption cause people to become smarter?

As you are probably suspecting, to show a causal link between chocolate and human cognition, a simple correlation and trend analysis are not enough. But what is missing?

- Causal Mechanism

In fact the sduty of Aloys LeoPrinz, (2020) provides a compelling theory that claims that because of the effects of flavonoids and caffeine has a positive effect on cognition and the dopaminergic reward system of the human brain. However, his paper does not provide the nuances about how come the flavoids and caffeine interact with a particular area(s) of the brain to yield that effect. In fact, his empirical study does not provide any biological evidence supporting that claim.

- Data

The study uses observational data, and does not solve the problem of self-selection and confounding variables. Moreover, the unit of observation (countries) is quite disconnected from the unit of analysis (Nobel laureates winners). That is, the study attempts to describe a causal mechanism that occurs at the micro level, namely, in the brain of Nobel Prize winners. In other words, he is using a macro data at the country level to draw conclusions about the brain of researchers.

- Endogeneity

The study does not controls for important confounding variables such as natural ability and the level of education of individuals. Also, there is no account for motivation and the number of weekly hours that researchers invest in their work. The lack of these controls, induces doubts in the estimation because they are important determinants of research productivity. Furthermore, the data has a problem of self-selection, because individuals are choosing to consume chocolate or coffee. Henceforth, we can observe the outcome of individuals of similar characteristics that do not consume coffee or chocolate (control or counterfactual group).

Social Norms and Energy Consumption.

The study of Schultz, Nolan, Et. Al, (2017) conducts an experiment on 290 households in San Marcos, CA, USA. The experiment was design to analyze the effect of two different kinds of social norms. One group was treated with an intervention that induce a “descriptive norm”, namely, the group was given information on their energy consumption compare to the average consumption of the neighborhood. The average consumption, has implicitly, a social norm given that individuals tend to have conformity with the behavior of their peers. The second group, was treated with another norm called the “injunctive norm” that embodies the perceptions of what is commonly right or wrong in a given situation. The core of the analysis is then to measure the effect of the two norms before and after the treatment.

- Causal Mechanism

The study uses the theoretical framework of “Focus theory” that predicts that if only one of the two types of norms is prominent in an individual’s consciousness, it will exert the stronger influence on behavior (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). The theory thus prescribe that the group treated with a “descriptive norm” will increase and decrease their energy consumption towards the mean. In contrast, the group that is treated with an “injunctive norm” should change the behavior only if they receive a negative signal (a sad face) when their consumption is above the mean, but not the other way around (boomerang effect).

- Data

The study uses experimental data because the treatment (social norm) is allocated randomly. The experimental data has the advantage of removing the problem of self-selection and the variable of interest \(X\), the social norm, is, by virtue of the random assignment, uncorrelated with other determinants \(Z\), of the energy consumption \(Y\).

- Endogeneity

The study only derives conclusions based on a difference in means, and they do not assess the effects of other factors that might drive the change of behavior, for instance, unemployment during the period of observation or absence in the household due to holidays or work. Further, it is not clear that the two groups were completely isolated from one another. The causal-mechanism depends on the prominence of one of the norms in the mind of the individuals. However, neighborhoods are typically well-know to communicate and interact among themselves, henceforth, it is not unlikely that a norm affected more than one household.

References

</div>